And then he was gone

#11—When there's no closure, just hope.

Welcome to Mind Flexing, your weekly thought expedition to everywhere and anywhere. Strap on your boots (or put your feet up), take a deep breath, and let’s get flexing.

It’s been a while since I thought of Habtamu. I don’t know what triggered it, perhaps it was exhaustion. But somewhere amid the evening chores and mundane rituals, his 8-year-old face flashed through my thoughts like a lightening strike, the type that stays above the clouds lighting the sky in silence, always out of reach, tugging my doleful heart.

Twenty-one years have passed since I first saw his photo—his little face, cheeks round with youthfulness and with the serious look of a child doing what he’s told, but without understanding. He was presented on a long orange card, folded in half so that it stood on its ends, and displayed on a table amid 40 or so other children.

I was working part-time at a jewellery store in Sydney’s Pitt Street Mall to financially compliment my ‘real’ job at a major radio station, where I had just risen to the ranks of the actually-being-paid. I mostly wrote community service announcements and recorded the traffic reporter’s audio while waiting for the next opportunity to arise. At the jewellery store interview, the manager had proudly declared the store to have the most expensive shopfront in the Southern Hemisphere—a calculation they’d presumably come to by combining the store’s rent with the value of the window’s assets: diamonds. The shopfront has long since gone.

The diamond section was by far the best part of the store to work in because it was the only part to have a window; a large window that faced the mall, with its scurrying people, buskers, sitting-down-sandwich-eaters and window shoppers.

And there I was on a light-filled day in 2003, standing behind my window, when a woman from the charity World Vision set up a table of children’s faces outside, entreating the privileged to sponsor them. I paid little attention at first. But as the morning wore on, and with few customers through the door, I had begun to know the children’s faces quite well.

Passing the table on my lunchbreak, I stopped to read the descriptions. The children, from all over the world, were mostly aged about five, and some were already in school.

Habtamu, wide eyed and serious, caught my attention. At eight-years-old, he was the oldest displayed. He worked with his family growing vegetables in Ethiopia and he wanted to go to school.

I walked on.

As the hours passed, the little faces on the table slowly disappeared, each having stolen the heart of some passerby and gone home in their pocket. By late afternoon, the table was almost empty, bar a few children, and Habtamu. I couldn’t bear it. I couldn’t leave this eight-year-old who grew vegetables and longed for an education unwanted on the table, so I signed the form and was handed his card.

I immediately had regrets, not about Habtamu, but about the Christian missionaries that now had so much sway in his community. I would have felt more comfortable if religion was kept out of it. The saving grace was that Kochere, the region of Ethiopia Habtamu was from, already appeared to be majority Christian.

I wouldn’t say I had a close relationship with my sponsored child. I, with important things that those in their early twenties must do, like partying, only wrote to him on a few occasions over the 15 years we were paired. But it was a good relationship. World Vision would send me annual updates, with vague details like, ‘I like playing soccer’. There were often little illustrations in pen, mostly of a house, purportedly drawn by Habtamu, but which I am sure were the works of the Kochere case worker. The drawings and handwriting didn’t change in all those years, despite Habtamu growing from a boy into a young man.

The good news was that Habtamu started school, and over the years the vague reports stated that he wanted to become a teacher.

Every two years or so, I’d be sent a photo of Habtamu. These were always my favourite things to receive and I’d study them to see how much he’d grown. He was often smiling, with a friend, posed in front of the vibrant green foliage of some exotic plant in the fertile farming region he called home.

The last photo I received of Habtamu was in 2016. Now about 21, he was crouched wearing a neat collared shirt and red shoes in front of a bush of yellow African senna flowers. He looked like a confident and capable young man.

I began to assume the sponsorship would soon end, after all, Habtamu was no longer a child. The vague updates said he was still in school, and I thought that a good enough reason to continue. But I half expected a letter any moment, thanking me for my sponsorship and informing me that Habtamu had happily graduated to become a teacher.

The letter came in September 2018, but it was like a shooting pain.

The Kochere project was closing down. There was a humanitarian crisis. World Vision’s resources were to be deployed elsewhere. They were unable to provide any information about those in Kochere. The region had become volatile, a new government had been installed, rebels were clashing with the army, drought and famine were setting in and amidst all this, refugees were flooding in from South Sudan, Somalia and Eritrea to escape their own conflicts.

The tether had been sorrowfully slashed. In my world, Habtamu was gone.

If things weren’t already bad, two years later, civil war broke out in northern Ethiopia between government forces and the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF), a former ruling party that had been labelled terrorists. The war lasted two years before a truce was called in November 2022, but instability remains.

The number of dead from the Tigray War will never be known, but various sides have estimates that range from 162,000 to 800,000, with the likely number thought to be around 600,000. Even at its lowest estimate, it’s a shocking figure and a tragedy that was ignored by a world preoccupied with COVID 19 and a tendency to turn a blind eye to Africa’s sufferings.

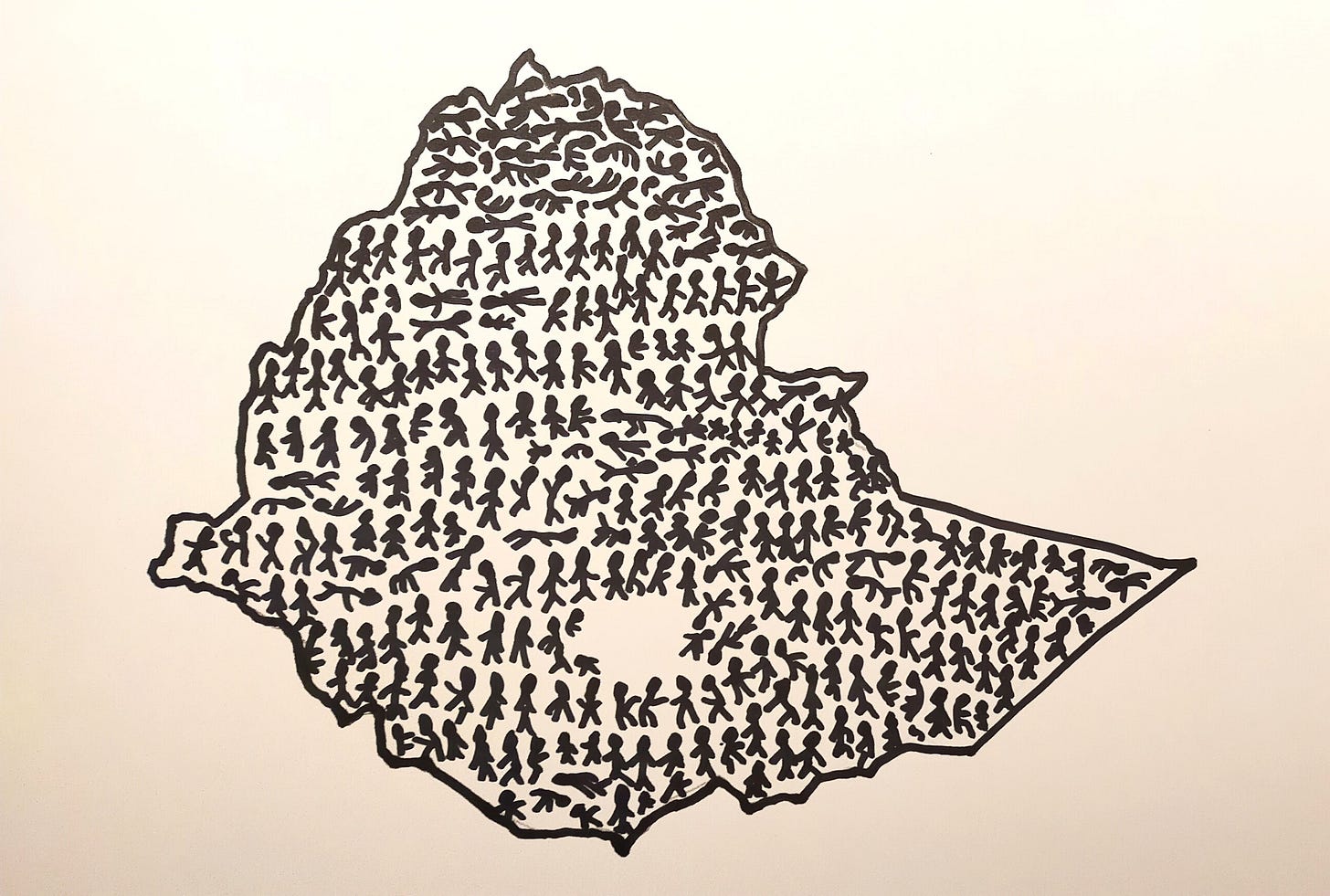

Today, there are about 3.8 million internally displaced people (IDPs) in Ethiopia, and almost 1 million refugees. More than 20 million people in Ethiopia required aid in 2023.

Where Habtamu fits in all this suffering, I don’t know. But because of him, I haven’t turned a blind eye. When you sponsor a child, you do so with a naïve expectation that their life will turn out alright. Naïve, but worth a try. All I have is hope that the young eight-year-old who grew vegetables and longed for an education found his way; that the confident young man with the world at his feet, landed on his, and that right now, somewhere in Kochere, there’s a class full of children looking up to a teacher named Habtamu Tadisse.

I need to think that.

Things I’ve enjoyed reading on Substack this past week:

Postcard from Adelaide—by Maggie MacKellar

Maggie talks about her time at the Adelaide Writers Festival and her novel, Graft, making the long list for the Stella Prize. Congratulations Maggie!

The Empty Boat—by Chuang Tzu via Poetic Outlaws

A thought by Chuang Tzu, a Chinese philosopher considered to be one of the key figures in Taoism.

A touch of genius—by Ann Kennedy Smith

Another read by Ann this week to celebrate women’s history month. This essay explores the young author Amy Levy, described by Oscar Wilde as having ‘a touch of genius’.

Thank you for Mind Flexing with me. If you enjoyed this essay, please subscribe, comment below, show some ❤️, or help me get this new publication off the ground by sharing it with someone you think would appreciate it.

I’ll be back next week. Until then, keep 💪.

Amazing read Alia…keep going!!