Two little known pasts shaping modern Australia

#29—A fun look at the origins of two elements of modern Australia.

Welcome to Mind Flexing, your weekly thought expedition to everywhere and anywhere. Strap on your boots (or put your feet up), take a deep breath, and let’s get flexing.

It’s NAIDOC Week—a week in which we celebrate the First Nations cultures of Australia—and in keeping with the spirit of that celebration, which is to spread awareness of Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander culture and issues, I thought I would share some fun insights into how the ancient cultures of this land have shaped two aspects of modern Australia that may not seem obvious, and which many Australians aren’t aware of.

First Nations Peoples designed Australia’s road network

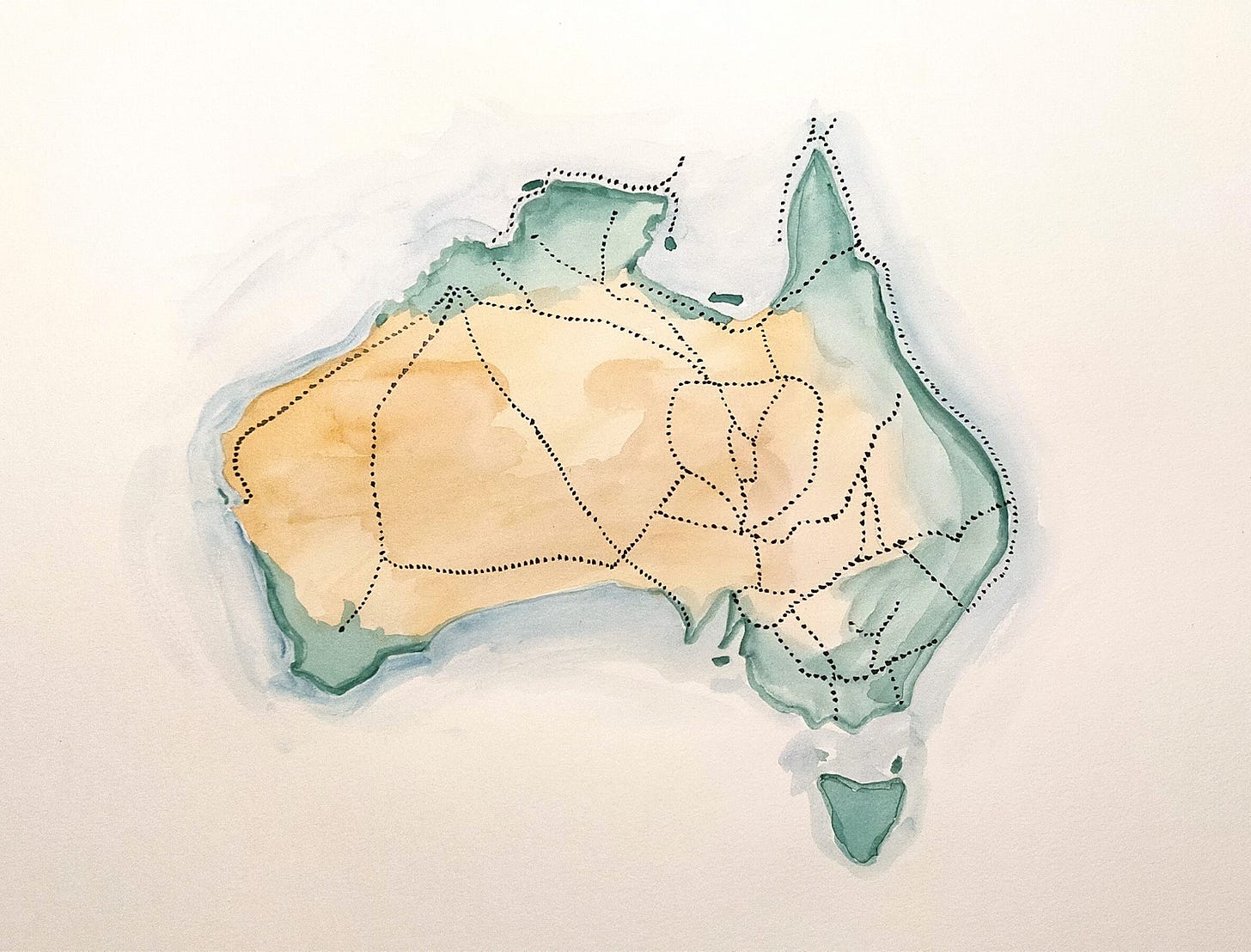

This one is my favourite because it’s so glaringly obvious when you think about it. Consider a road map of Australia, with its wide open, seemingly empty spaces (I can tell you now, they are in fact filled with cows), and note the network of lines that traverse the land from east to west, north and south, intersecting in places and travelling alone through the most rugged of landscapes in others. Notice the secondary roads in particular—the thinner brown lines connecting outback towns, some with people, some with memories of people. Many of these key roads and highways that connect landmarks and towns—particularly in remote regions—are much older than most people realise.

When the colonists arrived and began to expand their reaches across the country, thirstily laying claim to grazing lands far and wide, they didn’t reinvent the wheel by hacking through untamed bush; no, for the most part, they travelled along existing routes—routes first navigated tens of thousands of years earlier by the continent’s First Nations peoples and worn by feet every year since for trade, ceremony or marriage. These routes are known as songlines, and in many cases, Aboriginal guides who knew these songlines showed the colonists the way.

Songlines are such dynamic wonders; each is a remarkable library of knowledge that spans every aspect of culture and Country. On a practical level, they are verbal maps that detail the features of land, water, and sky that must be followed to navigate vast distances across the continent. That’s remarkable in itself, but songlines are so such more than that—they encompass all essence of existence told through epic Dreaming stories of the Creator Beings that travelled these routes, shaping the landscape. Within these stories are lessons, sacred sites, cultural law and lore. Even more fascinating is that someone from a different language group didn’t necessarily need to understand the language of a songline to understand its directions—the rhythm of the song formed a melodic contour map of the land that transcended the many language groups a line might travel. It’s a truly beautiful and profound concept, to know a place by its rhythm, by the way it makes you feel, and for this feeling to be universally understood by those who know how to listen.

The depth of information contained within a single songline is immense, which is why these stories were imprinted with song as a memory aide. In the same way that a chord can spark the memory of song lyrics you haven’t heard since you were a child, singing these ancient dreaming stories ensured they could be remembered and passed down through generations over thousands of years. Often, other memory aides, such as dance or star constellations, were also used.

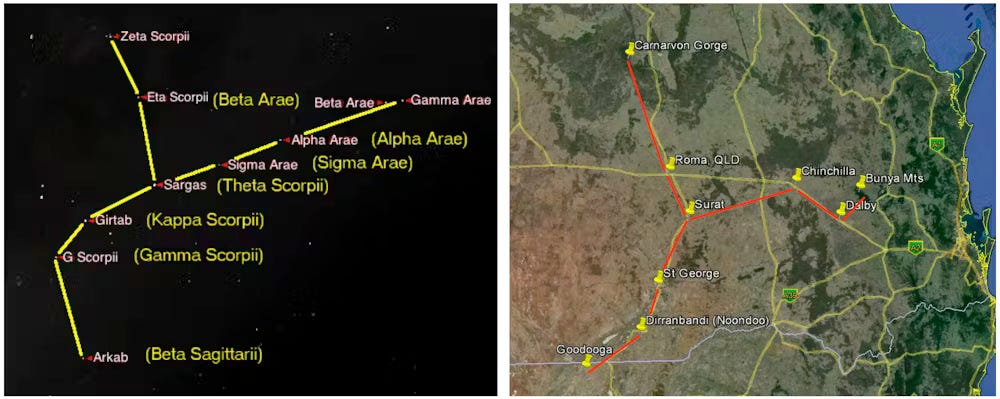

The star maps are particularly important memory aides and were used when teaching the songline to others, but not in the way most would imagine; the star constellation linked to a story didn’t indicate the shape of the route, but rather, its waypoints—that is, the number of key landmarks along the way. Many songlines, although not all, incorporated star maps in this way.

So back to those colonists ‘discovering’ the continent with their guides along these ancient routes. Much of the time, they were following these songlines and stopping to camp in existing campsites. Corrobboree sites were particularly useful because of the large cleared and flattened space and resourceful locations. Towns were often established around such sites because of their convenience and many corrobboree grounds later became racetracks or sporting ovals. Over time, the songlines connecting these places grew wider, eventually becoming roads. You can see how this works in this star map and songline outlined in research by academic Robert Fuller, in which he depicts the star map between Goodooga, Carnarvon Gorge and the Bunya Mountains in Queensland. When the star map is matched to the landmarks in the songline then overlaid on a road map, the correlation between the roads and landmarks becomes evident.

And so it is in this way that a significant number of Australia’s roads are based on ancient pathways, many of which are reflected in the stars.

Iconic ‘marks’ existed long before Aussie Rules Football

Long before the first white person ever set foot on Australian soil, a rather popular ball game called Marn-grook (meaning ball game in Woiwurung) was played throughout much of the continent and, later when squatters colonised the southern parts of Australia, this vibrantly spectacular sport was frequently witnessed in Victoria, NSW and South Australia. It’s probable that rules varied across Nations, but in general, Marn-grook could be played by men, women, and children, often organised into competitions of equal size and weight, in which two teams based on kinship would play against each other. Team sizes could vary, with reports of more than 100 participants in some games spread over a large playing space, and the games could last for hours. The winner would be determined by agreement in which team played the best, often decided by which team dominated ball possession, kicked the highest or the longest. To play the game, participants would drop a ball made of possum-fur twine and, before it could touch the ground, punt-kick it high into the air using the instep of their foot, with players then scrambling to catch the ball—some documented to have jumped one and a half metres into the air to do so. The person who caught the ball would then punt-kick it again.

For those familiar with Australian Rules Football (AFL), the images of punt-kicks and soaring into the air to catch the ball—a spectacular mark—will not be lost on you, and this is where things get a little controversial because it is widely believed that these element of Marn-grook influenced the Australian code. Of course, it shouldn’t be controversial, but it has never been formally recognised because of those who argue that those who wrote the rules didn’t specify that this was the case. The thing is, there’s no written record that specifies anything influencing the rules, and the game didn’t exactly materialise out of thin air. Could it be possible that two separate games of football that developed in the exact same part of the world could share an eerily similar key element of their game while bearing no relation to each other? Why yes, anything’s possible. But the balance of probability shrinks significantly the more you dig into it.

Here’s what we do know: Thomas Wills, the key influencer of the four sportsmen who wrote the first rules of the game in 1859, grew up on a station in the Western district of Victoria around what’s now called Ararat, where written records show that Marn-grook was played by the local Mukjarrawaint people. In one record, Will’s father, Horatio Wills, said:

‘…this land for some considerable time back an area of general rendezvous’ for the local Indigenous peoples, a place where corroborees, games and other entertainments were traditionally held including football.’

Not only did Tom Wills grow up in this setting, but family correspondence shows he spoke the Mukjarrawaint language and, as the only white child in the area, grew up playing with the Mukjarrawaint children. As a teenager, he had been sent to study at Rugby in England and intimately knew the rules of the type of football played at that school (rules varied across schools and had to be agreed upon before inter-school games). He was an exceptional cricketer and footballer (he later led an Aboriginal cricket team on an Australian tour as its captain and coach), and he was also known as a rule-bending larrikin.

There is no doubt that the rules of AFL were mostly influenced by those of the football codes played at various English public schools, such as Rugby, Cambridge and Dublin University, and marks existed in these games. But there is also no doubt that Tom Wills would have been familiar with Marn-grook—he likely grew up playing it with the Mukjarrawaint children—and there is a very high probability that he, and other Victorian players, would have been influenced by the punt-kicks and spectacular marks they had witnessed in these traditional games. That this style of kicking and marking should creep in to the way Victorians played AFL is, on the balance of probability, not a coincidence. If anything, it would be more remarkable if there were no connection between the two.

But what’s more impressive than any of this is that Marn-grook is quite possibly the oldest surviving ball sport in the world. We don’t know when it was first played, but its wide distribution across the continent and its existence in a culture that extends back at least 65,000 years, suggests it has a deep-rooted history, most likely older than the ancient ball sports that originated in Mesoamerica 3500 years ago and are credited with this title.

Things I’ve enjoyed on Substack this week:

-

When a trip into regional Western Australia doesn’t go to plan, best to stop to get a Parmi.

-

I have to agree with Rick’s sentiment toward Krispy Kreme doughnuts.

-

Veteran reporter Hugh Lunn describes how he channeled George Orwell when writing his books.

Etymology Monday

For those who missed it, this week’s word is:

story

Thank you for Mind Flexing with me. If you enjoyed this essay, please subscribe, comment, click the ❤️ button, or share it with someone who would appreciate it. I’ll be back next week. Until then, keep 💪.

Two great topics here, Alia. The roles of poetry/song, dance, rhythm and reference to natural features in codifying knowledge before (and alongside) literacy are endlessly fascinating to me, and still as potent today as they ever were, I think. In a world where so much knowledge is externalised to digital devices, we desperately need ways to re-internalise knowledge (and literature in its widest sense), or we risk losing aspects of our human identity and our relationship with our world.

The Marn-Grook/AFL evolution has a parallel in North America, where the Indigenous game Baggataway eventually evolved into the modern game of Lacrosse.