It’s been 56 years since humans first walked the silvery rock of the moon, hatching from our earthy bounds to stand on the surface of a heavenly body. How remarkable an achievement. How fantastical. And yet, not in my entire lifetime have I witnessed such a feat. Over three years, six Apollo missions staked the stars and stripes on the moon, and then it all stopped.

The moon was full and golden this past weekend, its light breaking through the windows to drag me outside. In the darkness of my little valley, where the town lights cannot reach, each full moon awakes a spectral world of silvery shapes and moon shadows so vivid one can walk around as if it were day. I watched the moon weave between the naked branches of winter as it tangoed with the earth—its gravitas forever pushing and pulling the ocean into a throbbing, beating heart. I squinted my eyes and tried to make out its features through its dazzling brilliance; The Sea of Tranquillity, The Ocean of Storms, the Lunar Highlands, places in its mid to upper regions where humans have walked before. From these places, my eyes travelled down some 1,800km to the moon’s South Pole, and paused. It is here, within two short years (if all goes to plan) that humans will once again touch down and shuffle through the moon dust in their space boots. Then in a few short more, they will build a moon base; a gateway to Mars and beyond, a collection of modular bits and bobs imperceptible from earth. There is ice frozen in the shadowy craters of the south. Water. A source for hydrogen rocket fuel. And there are minerals.

Who will get to them first?

Tucked deep within the edifices of our modern existence has been this sense of inevitability; that humans would go back to not just walk, but to colonise our lunar satellite. To build a space base for the ‘benefit of all peoples’. The United Nations’ Outer Space Treaty insists on things like that; that space exploration be for ‘peaceful purposes’, that it cannot be claimed or owned, that it is ‘the province of all mankind’, and that ‘All stations, installations, equipment and space vehicles on the Moon and other celestial bodies shall be open to representatives of other States Parties to the Treaty on a basis of reciprocity.’ Imagine that, the whole world sharing. It’s an idyllic sentiment, I’ll give it that.

Since 1967, 117 countries have ratified the Outer Space Treaty, including the US, Russia, and China. It’s a number that has grown by the year as space becomes crucial to the current wave of economic, military and communications development. This treaty is an important and very outdated document that means everything and nothing. Everything, because the ideas presented in it are just. And nothing, because (not only is it full of loopholes, but) enforcing it is near impossible. A UN attempt in 1979 to introduce the idea that a separate governing body be responsible for activities on the moon and that all moon resources be shared equally, failed miserably. The Moon Agreement still exists but means very little given none of the major players ratified it.

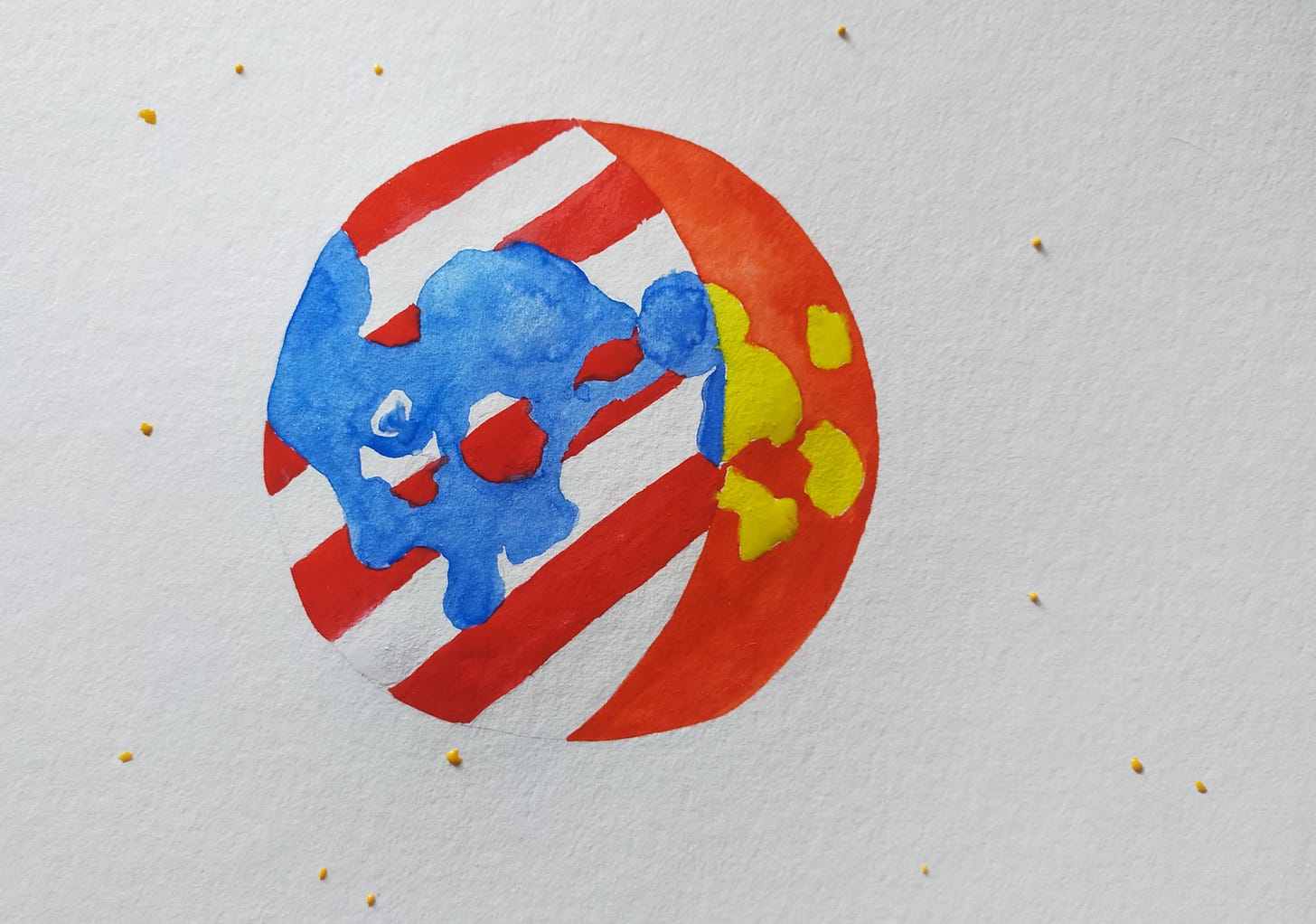

Its cracks are widening. There are two separate planned bases on the moon: the US-led Artemis Base Camp and the China-led International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), which has the assistance of Russia’s Roscosmos. Both bases are supposedly for the good of mankind, and both have very similar goals, yet the two groups are not, and do not intend to work together. Separately, they are growing their list of signatories to their own almost identical accords, splitting the world of space development in two.

In 2011, the US passed a bill barring NASA from working with China on the basis of national security, and probably with good reason, so it was never going to be likely that China would come begging to join Artemis, and with Russia by its side, it didn’t have to. The move effectively prevented China from using the International Space Station and led China to build its own—the Tiangong Space Station, completed in 2022 and continually inhabited by taikonauts.

Both the US and China pitch their moon projects as having the higher moral ground: China accuses the US of commercialising space for its own economic benefit, and the US is suspicious of China’s military intentions.

NASA believes there is a real possibility that if China were to reach the limited area of water supply first, that the US would be prevented from accessing it. China shares similar concerns, and those concerns carry weight under the Trump regime. Meanwhile, both projects are going tit for tat. Earlier this year, Russia and China spoke separately about their intentions to place a nuclear reactor on the moon sometime after 2033 to power their research station. Then this month, the US confirmed it was increasing the size of its nuclear power capacity on the moon from 40kW to 100kW, with a plan to install it by 2030.

As it stands, the US appears to be on track to reach the South Pole first, with the Artemis III crewed mission scheduled to land there in mid-2027 (although it’s already two years behind schedule and could face further delays due to unresolved challenges with SpaceX’s Starship). The ILRS is less transparent with its progress, but has said the preparation of surface facilities to support crewed landings would begin in 2031. Nevertheless, China’s uncanny ability to execute projects at breakneck speed is keeping the US on its toes.

The Space Race has well and truly restarted. How open to reciprocity will our contestants be? Will their endeavours be for the ‘benefit of all peoples’? Or just some?

And where, in the UN Treaty, does our commercial sector fit? Our Elon Musks and Jeff Bezos’s, our Lockheed Martins and Rocket Labs.

A record US$613 billion was invested in the global space economy in 2024, and 78% of this was from the commercial sector. Space activity is storming ahead. In the first six months of 2025, a space launch took place every 28 hours—a record 149 liftoffs, of which more than half were made by SpaceX alone.

There are about 10,000 active satellites now orbiting the earth, more if you count the space junk. Soon, those satellites will be joined by the missile interceptors and laser beams of Trump’s Golden Dome defence shield. Weapons in space. Now that’s most definitely pushing the boundaries of the Outer Space Treaty, although the commercial manufacturer Lockheed Martin assures us it is ‘a revolutionary concept to further the goals of peace through strength…’. Silly me, I guess it’s OK then.

It was a waning gibbous moon last night as the earth’s shadow crept across the lunar surface. In a few days the South Pole will be submerged in darkness until it begins to reveal itself once more; a new moon. And soon, a new flag will be planted there, and new colour footage of astronauts—or cosmonauts or taikonauts—bouncing in moon dust will beam down around the world.

I try to think beyond all the political jockeying in the US and China’s new Cold War for world domination and focus on the possibilities that will emerge from all this. It has been 53 years since humans last walked on the moon, and soon, those of my generation will witness this for ourselves. But we’re very likely to witness something more. The goals of Artemis are very clear; in the next 15 to 20 years, we will likely see humans take their very first steps on Mars. We will reach the red planet. Mars, some 225 million kilometres away, that tiny flickering red light in the sky.

So far from home. How fragile our little blue planet must look from way over there.

Thank you for Mind Flexing with me. If you enjoyed this essay, please subscribe on Substack or your favourite podcast app, comment, click the ❤️ button, or share it with someone who would appreciate it. I’ll be back in a fortnight. Until then, keep 💪